Reviewing M&A Valuations: A Framework for Senior Executives to Ask the Right Questions When It Matters the Most

1. Introduction

Asking the right questions when reviewing M&A valuations is of utmost importance for senior executives.[1. See Mukherjee et al. (2004), Merger Motives and Target Valuation: A Survey of Evidence from CFOs, Journal of Applied Finance, Vol. 14, No. 2, Fall/Winter 2004, pp. 7-24; Evans (2002), Valuation Essentials for CFOs. Financial Executive, pp. 63-65; Nyborg/Mukhlynina (2012), The Choice of Valuation Techniques in Practice: Education versus Profession, SFI Working Paper, pp. 1-61.] However, in practice this is not always the case. According to Koller et al. (2010), “(n)ot all CEOs, business managers, and financial executives possess a deep knowledge of value”[2. Koller et al. (2010), Valuation – Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, Wiley, Back cover.], which could potentially be explained by their respective professional backgrounds and career paths, which not always include a history of deal making or by the observation that senior executives sometimes tend to be rather generalists than specialists.[3. See Lazear (2010), Leadership: A Personnel Economics Approach, NBER Working Paper No. 15918, pp. 1-35.]

Therefore, the following article aims at providing senior executives, who are not M&A or valuation experts, with a general framework that helps them to challenge M&A valuations. The framework outlines a variety of key areas which are part of valuation analyses and addresses several relevant questions that senior executives should ask when reviewing them. By knowing about these critical areas and by being able to challenge them, the reasonability of the derived enterprise and equity values can be better judged and an opinion can be formed whether the valuation conclusions make sense.

To illustrate the key areas of concern more comprehensive, the article makes reference to a hypothetical valuation case in which the standalone value of a privately held, potential acquisition candidate is determined. The valuation relies on a 5-year business plan plus a terminal value year, which forms the basis for a DCF valuation. Besides, the market approach was used to support the DCF valuation conclusion. As the article focuses rather on valuation methodologies and their application, and not on individual value drivers related to a firm’s business or operations, the presented guidelines can be equally applied across various industries and sectors.

2. Typical areas of concern in M&A valuation analyses

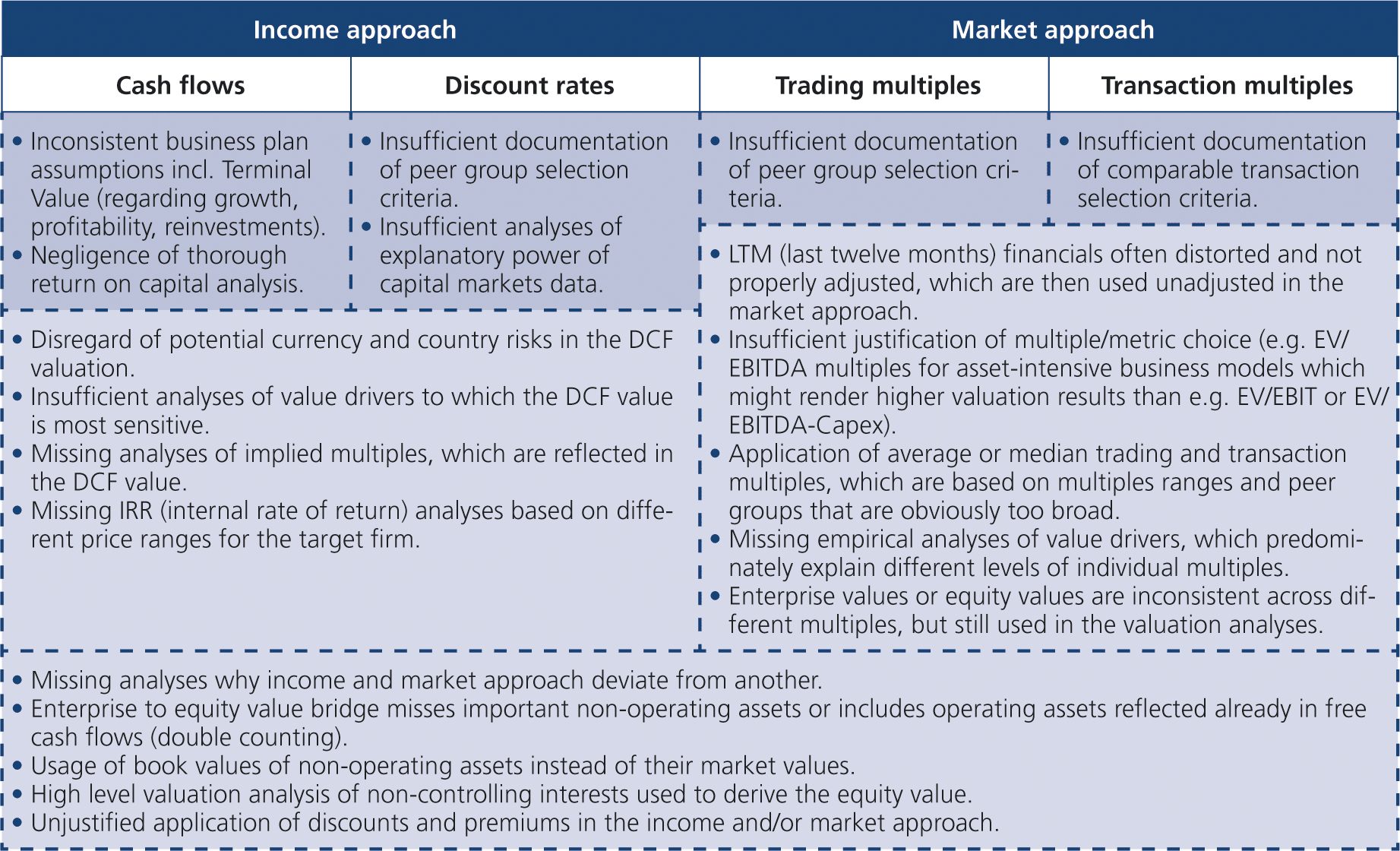

Based on the practical experience of the authors in performing M&A valuation analyses and in reviewing them, several areas of concern can be identified that can be considered recurring in practice. These areas of concern are summarized in figure 1 and further analyzed in more detail below.

Source: Own illustration

Area of concern 1:

Business plan assumptions are questionable due to apparent information asymmetries between the valuer and the valuation subject

Business plans, which are highly relevant when performing valuations based on future cash flows or trading multiples, usually represent the biggest area of concern in valuation reviews.[4. See Fazzini (2018), Business Valuation: Theory and Practice, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 31; Massari et al. (2016), Corporate Valuation: Measuring the Value of Companies in Turbulent Times, Wiley, pp. 18-53; Massari et al. (2014), The Valuation of Financial Companies: Tools and Techniques to Measure the Value of Banks, Insurance Companies and Other Financial Institutions, Wiley, p. 81.] This is predominately due to the valuer’s subjective assessments of the future performance of the valuation subject.[5. See Maynard (2005), Mergers and Acquisitions: Cases, Materials, and Problems, Wolters Kluwer, pp. 164-165; Larrabee/Voss (2012), Valuation Techniques: Discounted Cash Flow, Earnings Quality, Measures of Value Added, and Real Options, Wiley, p. 105.] The authors’ view on the subject matter is that challenging business plan assumptions should be of utmost importance for senior executives in valuation reviews.

Although being certainly challenging to argue against certain business plan assumptions due to apparent information asymmetries between the reviewer and valuation subject, there are certain ways to get more comfortable with expected growth rates and profitability margins, especially during a forward looking 2- to 3-year time frame. To benchmark business plan assumptions, the reviewer can analyze the historical performance pattern of the valuation subject, analyze how the overall sector of the valuation subject has developed and is forecasted to continue or use third party assessments (especially in analyst reports or from consensus estimates for publicly listed competitors or the overall industry).[6. See Geddes. (2002), Valuation and Investment Appraisal, Financial World Publishing, pp. 1-55.] Benchmarking should predominately include revenue growth rates, profitability margins, and reinvestment rates, as reinvestments could justify an above (industry) average increase in future earnings.[7. See BerryDunn, Using Industry Benchmarks to Establish Secure Negotiating Positions for Merger and Acquisition Purposes, White Paper, pp. 1-14.] Also, the analysis should be performed on the most granular level possible, e.g. benchmarking growth rates and margins of distinct divisions or business units to comparable peers for the respective end-markets served.

A proper analysis of Retun on Invested Capital (ROIC), Capital Employed (ROCE) or Return on Equity (ROE)-levels in the business plan can also be a valuable tool for the reviewer, helping to understand the reasonability of the business plan.[8. See Koller et al. (2010), Valuation – Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, Wiley, pp. 165-185.] However, this analysis gets often neglected when it comes to reviewing expectations in business plans. Making the argument that someone is overly optimistic is sometimes difficult to support, when arguing exclusively on the basis of ratio analysis (like growth rates or profitability margins). It is more meaningful to support this argumentation by looking at overall performance levels, represented by ROIC, ROCE and ROE, and arguing on the basis of the same.

Area of concern 2:

Discount rates in the income approach do not fully reflect the riskiness of the asset to be valued

The second set of material value drivers that should deserve enough attention of the reviewer refers to the selected risk-adjusted discount rate applied in the DCF valuation. Although the application of the text book WACC and CAPM formula should not be an issue for M&A and valuation professionals, additional risk premiums could be more of an issue in valuation analyses.[9. See Grabowski et al. (2017), 2017 Valuation Handbook: International Industry Cost of

Capital, Wiley, p. 68; Pratt/Grabowski (2010), Cost of Capital: Applications and Examples, Wiley, p. 436; Ogier et al. (2004), The Real Cost of Capital, Prentice Hall, pp. 133-135.] This holds particularly true for potential country risks and risks associated with the size or age of the valuation subject.[10. See Damodaran (2003), Measuring Company Exposure to Country Risk: Theory and Practice, NYU Stern School of Business Working Paper, pp. 1-29; Chincarini et al. (2016), The Life Cycle of Beta, EFMA Conference Paper, pp. 1-43.] With regards to country risks, reviewers need to decide whether an additional premium is warranted in the discount rate for being exposed to potential country risks that could emerge, for example, when investing in a foreign country or generating revenues in non-domestic currencies, and furthermore how this is accounted for.[11. See Kruschwitz et al. (2012), Damodaran’s Country Risk Premium: A Serious Critique,

Business Valuation Review, Vol. 31, Issue 2-3, pp. 75-84; Gleißner (2014), Kapitalmarktorientierte Unternehmensbewertung: Erkenntnisse der empirischen Kapitalmarktforschung und alternative Bewertungsmethoden, Corporate Finance 4/2014, pp. 151-167.] Not properly reflecting all risks in valuations will make a valuation subject appear more valuable than it actually is, due to the inverse relationship between discount rates and enterprise values. Other potential cost of capital adjustments, sometimes observable in third party valuations, refer to the size and age of the valuation subject.[12. See KPMG (2019), Cost of Capital Study 2019, Accessible: https://home.kpmg/de/en/

home/insights/2019/10/cost-of-capital-study-2019.html; Cheridito/Schneller (2008), Discounts and Premia in der Unternehmensbewertung, Der Schweizer Treuhänder, Vol. 6-7/2008, pp. 417-418; Chincarini et al. (2016), The Life Cycle of Beta, EFMA Conference Paper, pp. 1-43; KPMG (2019), Cost of Capital Study 2019, Accessible: https://home. kpmg/de/en/home/insights/2019/10/cost-of-capital-study-2019.html; empirical analyses for Germany are limited in number, see for example Hagemeister and Kempf (2010), CAPM und erwartete Renditen, Die Betriebswirtschaft, Vol. 70, No. 2, pp. 145-165] Based on some empirical evidence derived from individual capital markets, firms with smaller market capitalizations have performed better in terms of market returns than their larger counterparts.[13. See Fama/French (2012), Size, Value, and Momentum in international Stock Returns, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 105, Issue 3, pp. 457-472; Brückner et al. (2015), Non-U.S. Multi-Factor Data Sets Should be Used with Caution, Working Paper, pp. 1-36.] Besides, the systematic risk of a valuation subject can be partly explained by its age.[14. See Chincarini et al. (2016), The Life Cycle of Beta, EFMA Conference Paper, pp. 1-43.] So called size premiums have found their way into valuation analyses in several countries.[15. See KPMG (2019), Cost of Capital Study 2019, Accessible: https://home.kpmg/de/en/

home/insights/2019/10/cost-of-capital-study-2019.html; Cheridito/Schneller (2008), Discounts and Premia in der Unternehmensbewertung, Der Schweizer Treuhänder, Vol. 6-7/2008, pp. 416-422.] Also, in Germany there are diverging views around the reasonability and application of such size premiums in valuation analyses.[16. See Ballwieser (2018), Zur „Kunst“ der Verwendung von Bewertungszuschlägen und -abschlägen, Corporate Finance, Vol. 3-4/2018, pp. 61-72; Gleißner (2014), Kapitalmarktorientierte Unternehmensbewertung: Erkenntnisse der empirischen Kapitalmarktforschung und alternative Bewertungsmethoden, Corporate Finance Vol. 4/2014, pp. 151-167.] Although no general recommendation can be given at this point, empirical evidence from certain mature capital markets implies that firms with smaller market capitalizations have performed better over certain time periods than firms with larger market capitalizations, implying a return differential.

Area of concern 3:

Enterprise value derived from the income approach (DCF) deviates materially from the enterprise value derived from the market approach

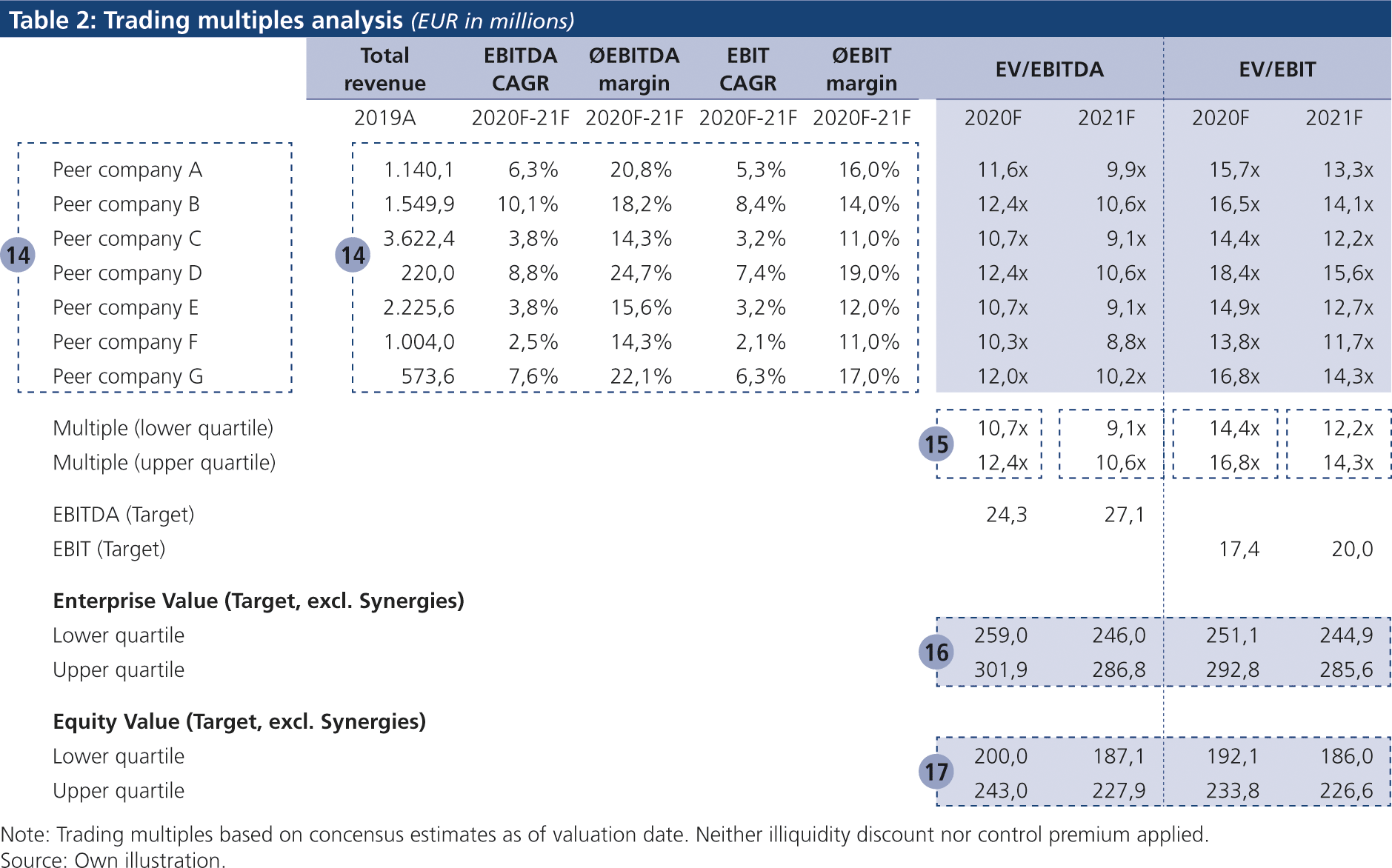

The authors highly recommend to pay close attention to the valuation results for a valuation subject derived from future cash flows (income approach) and from trading multiples (market approach) when reviewing valuation analyses. If the results from the income approach deviate materially from the results from the market approach, it raises the question of the sources for such discrepancies. Although trading multiples rather price the valuation subject and not derive an intrinsic value, results emerging from comparable companies can be used regularly as a meaningful benchmark for the income approach.[17. See Koller et al. (2010), Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, Wiley, pp. 313-332; Koller et al. (2005), The Right Role for Multiples in Valuation. Accessible: www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-right-role-for-multiples-in-valuation.] When reviewing valuations, the reviewer needs to understand why the enterprise value derived from the income approach is higher or lower compared to an enterprise value derived from trading multiples (like EV/EBITDA or EV/EBIT).

Key explanations for that observation could relate to using a business plan in which value drivers are reflected that are too optimistic or too conservative to those of publicly listed peer firms (i.e. business plan deviates from market view) or that the peer firms are not fully comparable to the valuation subject in terms of value drivers’ levels (i.e. peer group is too broad and not aligned to levels of value drivers of valuation subject).[18. See Kumar (2016), Valuation: Theories and Concepts, Elsevier, p. 189; Bernström (2014), Valuation: The Market Approach, Wiley, pp. 49-51; Koller et al. (2010), Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, Wiley, pp. 313-332.] Relevant value drivers usually refer to different revenue growth expectations, profitability margins, return on capital levels, reinvestment rates, and discount rates.[19. See Damodaran (2002), Investment Valuation, Wiley, pp. 453-466; Bernström (2014), Valuation: The Market Approach, Wiley, pp. 49-51.] A proper analysis of these drivers needs to be included not only in the business plan analysis, but also when it comes to selecting the most comparable peer firms. Not paying close attention to these selection criteria will result in a trading multiples range that is too wide and not meaningful for the valuation analysis. If not provided by the valuer, it is the responsibility of the reviewer to investigate such potential differences.

To get an initial sense of the reasonability of the DCF value conclusion, the reviewer can estimate the implied EV multiples that are reflected in the DCF value.[20. See Rosenbaum/Pearl (2013), Investment Banking, Wiley, p. 140.] To do so, he can use the enterprise value from the DCF analysis and divide it by the expected EBITDA or EBIT numbers for the first or the second forecast period. Thereafter, the implied multiples can be compared to the range of multiples observable on capital markets for comparable companies.[21. See Pignataro (2013), Financial Modeling and Valuation, Wiley, pp. 383-385.] The authors recommend projected performance figures and not actual ones for calculating implied multiples, as actuals can be distorted by material one-off items (for the valuation subject and peer firms). This surely can also hold true for forecasted figures, however the probability is much lower as one-off items (non-recurring items) usually emerge unplanned and should therefore most likely be not included in consensus estimates of financial analysts.[22. See Rosenbaum/Pearl (2013), Investment Banking, Wiley, pp. 47-49; Damodaran (2002), Investment Valuation, Wiley, pp. 240-244.] It needs to be added in this context however, that trading multiples represent the outcome of minority transactions on liquid capital markets. Therefore, adjustments in the form of discounts or premiums might become relevant.[23. See Pratt (2009), Business Valuation Discounts and Premiums, Wiley, pp. 1-40; Risius (2007), Business Valuation, ABA Publishing, pp. 152-162.]

Area of concern 4:

Enterprise to equity value bridge

When working with free cash flows to the firm (FCFF) in the income approach, a valuation subject’s net debt position needs to be subtracted from its enterprise value to derive the respective equity value. An imminent question is which components have to be reflected in the net debt position. The debt position typically includes all financial liabilities (short term and long term bank loans, bonds), other interest bearing liabilities (like shareholder loans), leases and unfunded pension obligations (if relevant).[24. See Damodaran (2002), Investment Valuation, Wiley, pp. 423-450.] Apart from these positions, the valuer needs to analyze whether any minority interests need be deducted. If identified, the minority interest needs to be valued separately and deducted from the enterprise value, as the related cash flows are fully reflected in the enterprise value of the valuation subject. When it comes to adding cash and cash equivalents, the authors recommend including only those “excess cash” positions that are considered non-operational (for example cash positions already declared as dividends for the last financial year, however not paid out yet). In case deemed to be operational, these balances should rather be reflected in working capital and not as a separate component in the enterprise value to equity bridge.[25. See Damodaran (2002), Investment Valuation, Wiley, pp. 423-450.] Besides, other potential non-operating assets and/or financial assets (like joint ventures, investment in associates) might be identified in the balance sheet of the valuation subject and not captured yet in the free cash flow derivation. Similar to the excess cash position, the market values of these non-operational assets and/or financial assets should be added to derive the equity value conclusion.

3. Potential questions to address when reviewing M&A valuation analyses

In the following, a hypothetical a hypothetical, simplified valuation analysis in which the standalone value (excl. synergies) of a privately held, potential acquisition candidate is outlined. The DCF valuation relies on a 5-year business plan plus a terminal value year, which forms the basis for a DCF valuation (WACC approach). Besides, the market approach was used to support the DCF valuation conclusion.

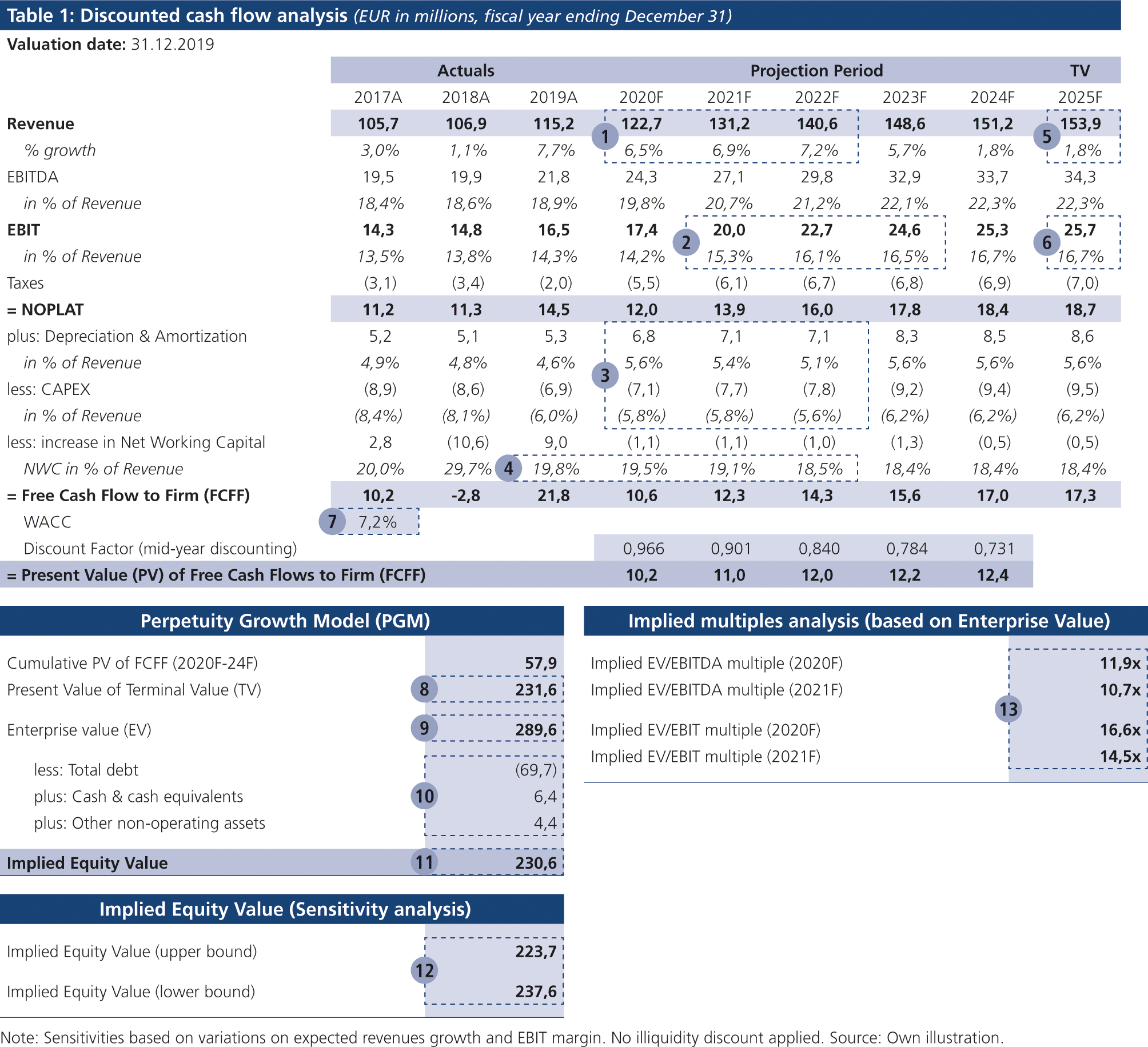

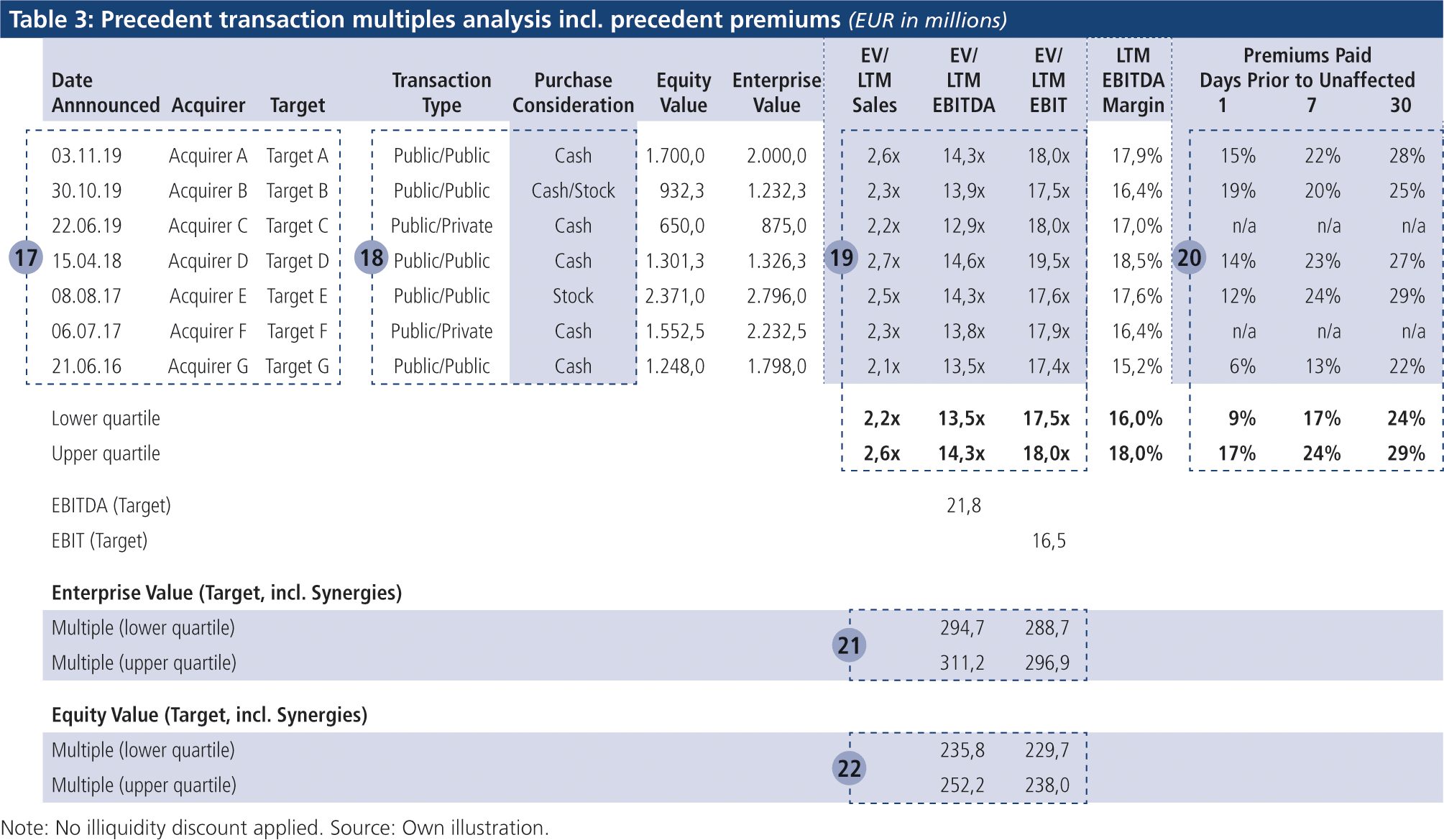

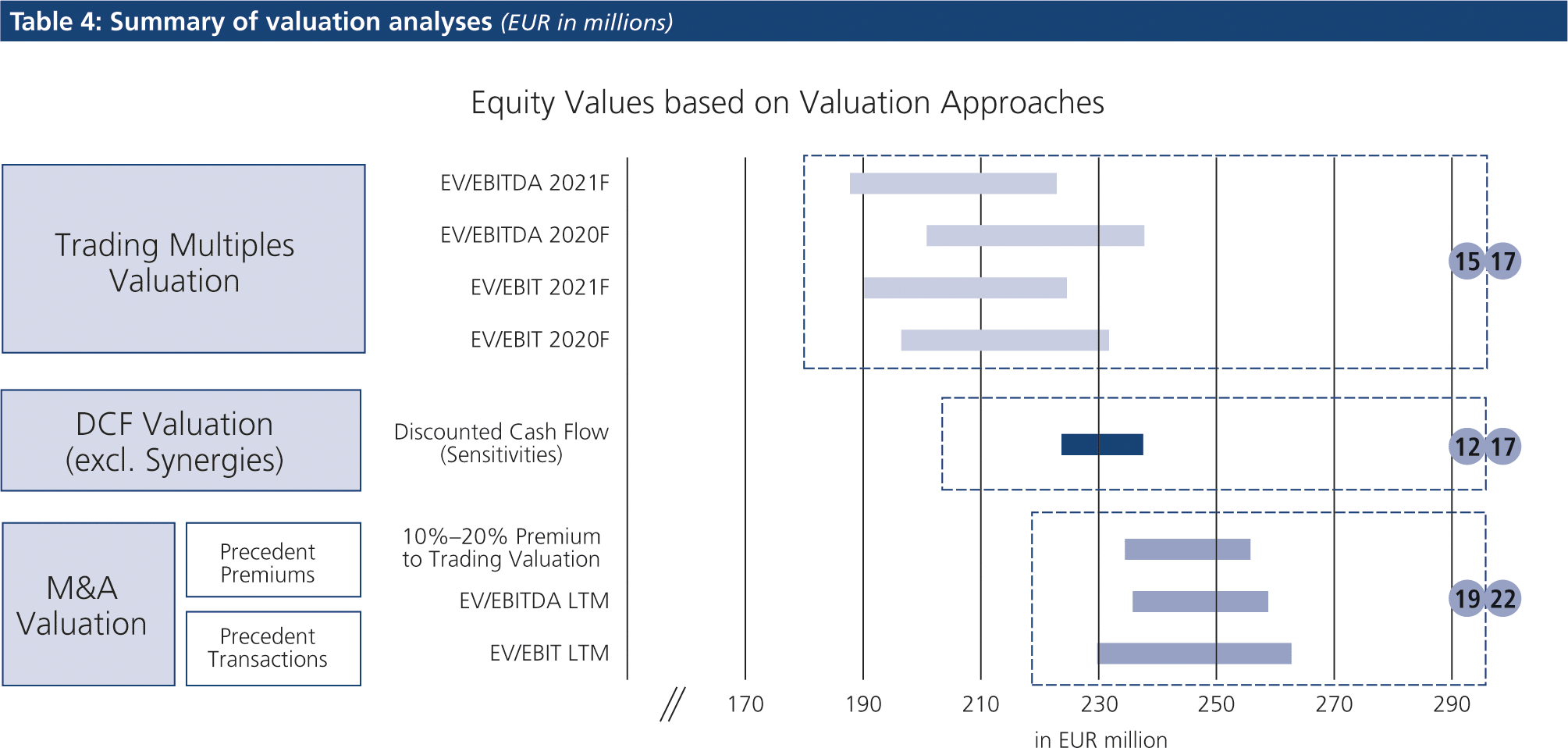

Table 1 (which can be found at the end of this article) summarizes the derivation of the free cash flows to the firm, the discount factors, the enterprise value, the net debt position, and the corresponding equity value as of the valuation date 31.12.2019, based on which potential review questions were formulated. The market approach was applied to support the valuation conclusion from the income approach. Both trading and transaction multiples were applied (see tables 2, 3 and 4).

Based on the DCF valuation analysis, the implied equity value amounts to EUR 230,6 million. The applied business plan expects that the financial performance of the target firm improves materially over the next years. The DCF valuation analysis applies a WACC of 7,2%. Total debt is estimated to amount to EUR 69,7 million as of the valuation date. Cash & cash equivalents amount to EUR 6,4 million. Besides, other non-operating assets in the amount of EUR 4,4 million are identified. The DCF analysis applies mid-year discounting. To derive the present value of the terminal value, a Perpetuity Growth Model (Gordon Growth Model) is applied.

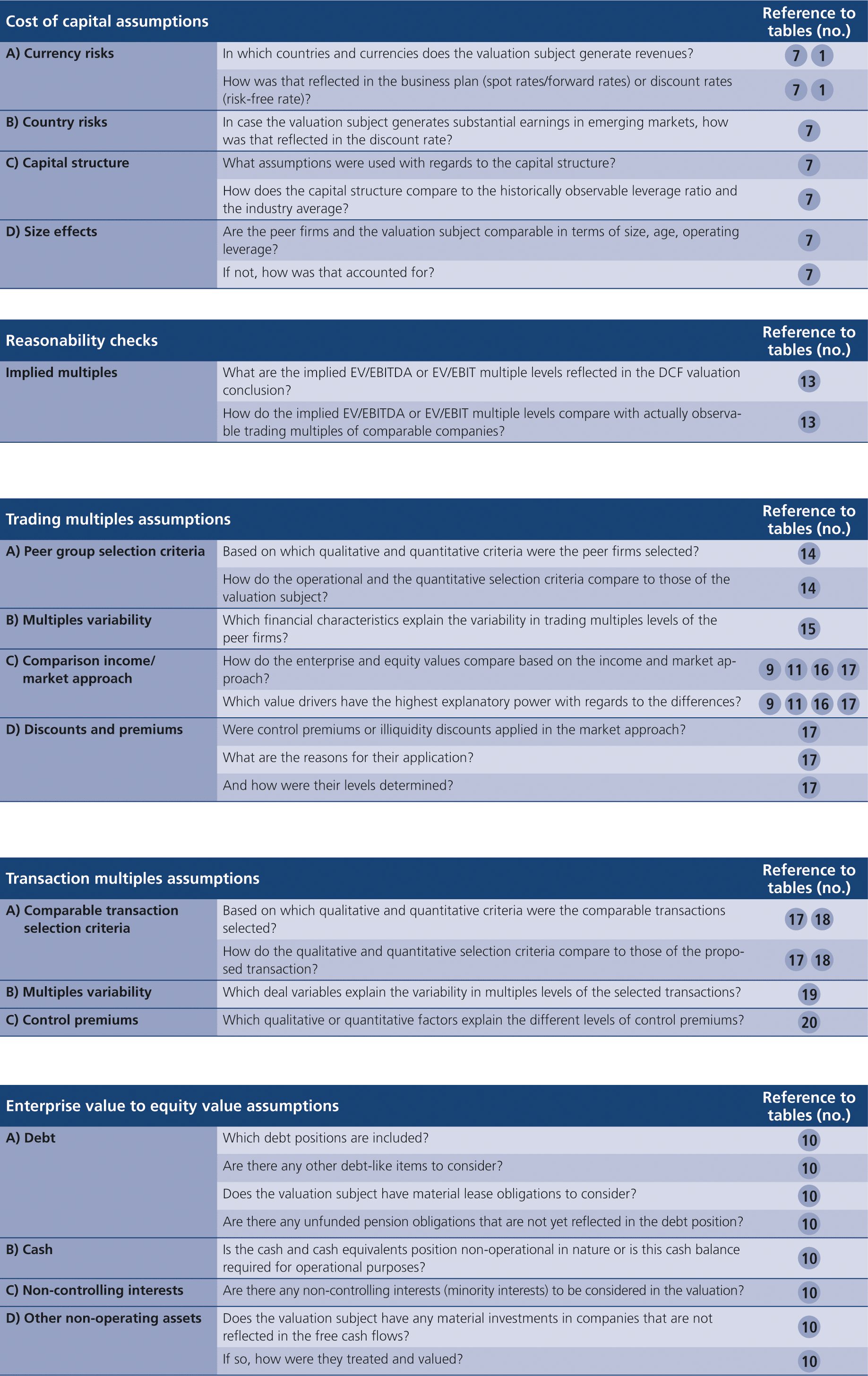

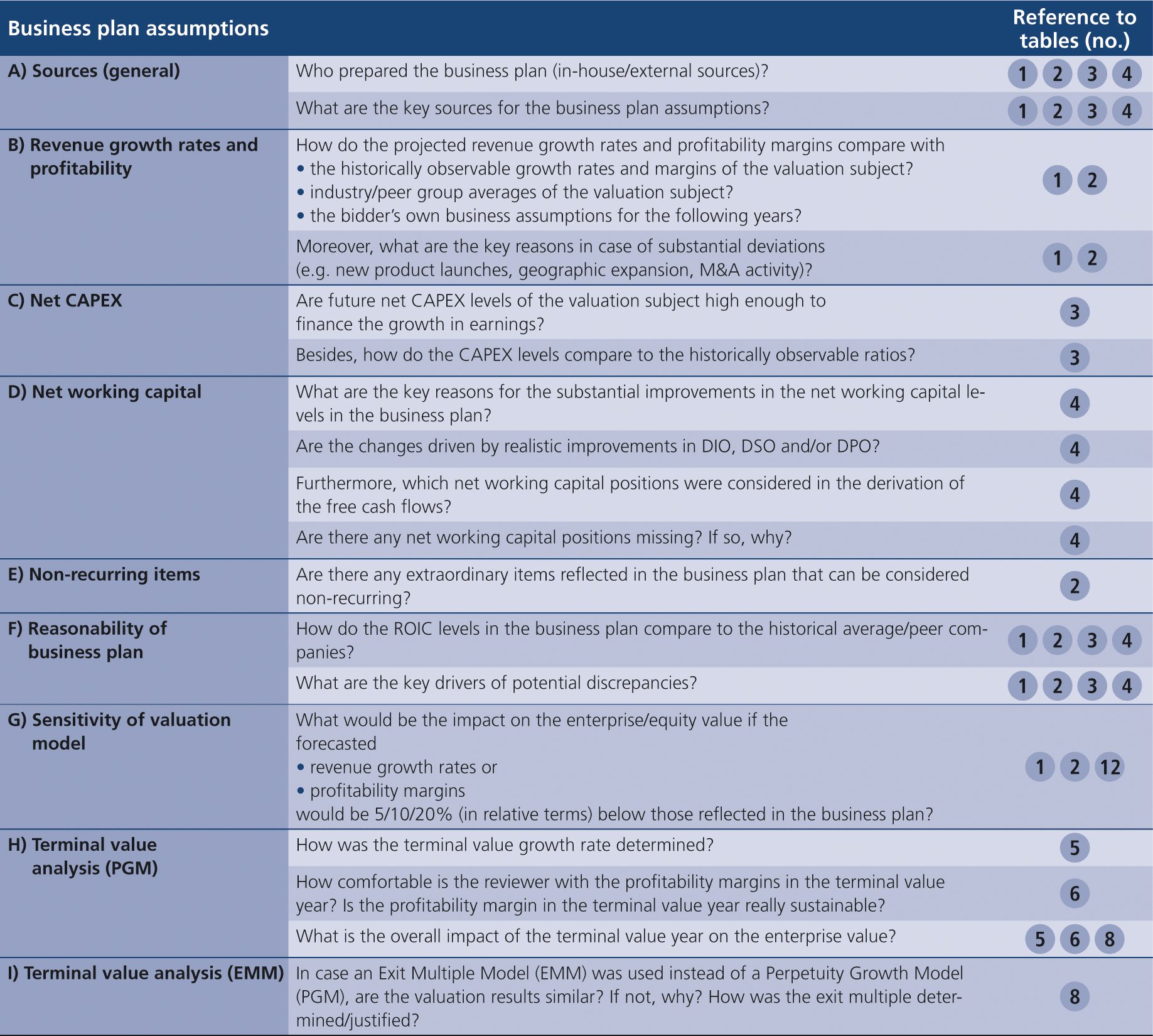

Based on the integrated case study, several topics should come to the attention of the reviewer of the valuation analyses, related to section 2 of this article. Tables 5–10 list a variety of relevant review questions which should help the reviewer to get a better understanding of the valuation analyses. The review questions, which focus on both the income and market approach, address the applied business plan assumptions, cost of capital assumptions, trading multiples assumptions, transaction multiples assumptions, as well as enterprise value to equity value assumptions. Besides, several suggestions how to analyze the reasonability of the derived enterprise and equity values are outlined.

Source: Own illustration

4. Conclusion

Understanding the reasonability of enterprise and equity values derived from the income and market approach is of essential importance for senior executives in today’s business world. Not only due to the relevance of a target’s purchase price to create or destroy value in M&A, but also from an accounting point of view, as the purchased assets and assumed liabilities including goodwill are to be recognized with their market values in the consolidated group accounts of the buyer. This means any overpayment could result in a potential goodwill impairment in the future.

Although senior executives do not have to be valuation experts in every technical aspect, they should be in the position to challenge critical valuation assumptions. Only then one can reduce the risk of material misjudgments made by third parties involved in deals, related to a lacking knowledge of the valuation subject or current and expected industry dynamics.

With this article, the authors wanted to lay out a general framework to ask the right questions when it matters the most. The framework focused on a variety of different areas of concern. This included a valuation subject’s business plan and cost of capital, which are the principal determinates of a valuation subject’s enterprise value. Besides, important aspects regarding high level reasonability checks to be applied by senior executives, as well as questions with regards to peer multiples and to bridging enterprise to equity values were addressed. Due to the technical complexity of some of these areas of concern, asking for support from independent third parties in large scale transactions is highly advisable.