M&A as an accelerator to achieve ESG targets in the Energy industry

In the past years, the notion of “sustainability” increasingly gained traction in the public and put pressure on companies to adjust their business to be more sustainable – across all industries and geographic regions. However, while a common interpretation of the term has typically been heavily weighted towards environmental protection efforts (e.g. CO2 or waste reduction), sustainability has a much broader meaning, covering also social and economic objectives such as poverty reduction, welfare and diversity. From a corporate perspective, various sustainability criteria are often summarized under the umbrella term ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance), which also addresses the governance aspect of implementing compliance, proper processes and incentives within firms.

1. ESG Fundamentals

In the past years, the notion of “sustainability” increasingly gained traction in the public and put pressure on companies to adjust their business to be more sustainable – across all industries and geographic regions. However, while a common interpretation of the term has typically been heavily weighted towards environmental protection efforts (e.g. CO2 or waste reduction), sustainability has a much broader meaning, covering also social and economic objectives such as poverty reduction, welfare and diversity. From a corporate perspective, various sustainability criteria are often summarized under the umbrella term ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance), which also addresses the governance aspect of implementing compliance, proper processes and incentives within firms.

The annual AlixPartners Disruption Index is a measure of the number and intensity of disruptive forces companies face: 45 percent of CEOs stated that ESG had an extreme impact on their organizations, a considerable increase from 27 percent in 2021.1 Private and business customers consider aspects of ESG in their buying decisions and inform themselves about the track record of the seller. Furthermore, employees may prefer to work for companies with credible and well-defined ESG values. Investors are increasingly restricting funding of companies with an unfavorable ESG performance both on equity as well on debt levels.

To increase transparency and accountability on efforts to improve ESG fundamentals within companies and avoid unrestricted overuse (including dubious classifications of all sorts of activities as “sustainable”, a practice for which the term “greenwashing” has been coined), regulatory frameworks have emerged. As an example, in the USA the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed regulation on climate and cyber security disclosures requiring companies to disclose their risks related to climate change as well as their greenhouse gas emissions. Separately, the European Commission adopted a proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. In addition to regulatory frameworks, various organizations have developed reporting frameworks, for example the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) or the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

It is controversial if stronger focus on ESG factors has immediate economic benefits. Such benefits might be dependent upon industry sector, the specific company situation and regulatory environment. However, ignoring ESG factors is not a viable option for companies. As we will discuss in more detail below, the Energy sector is a strong case-in-point here, where neither a definition of the strategy, investment or divestment decisions nor the financing can regularly be obtained without a clear ESG strategy. Therefore, for companies ESG transformed from a rather nice-to-have or necessary appendage to a strategic pillar of their business model.

2 ESG in Energy M&A deals

ESG also has a strong impact on the definition of M&A strategies in the Energy industry., where ESG considerations become in fact the key driver of a transaction. One important rationale is the idea of acceleration. Just as regular transactions allow faster growth of a company, acquiring certain assets may act as an accelerator to achieve the strategic goal of (increased) ESG compliance. Lengthy planning and approval processes render it almost impossible to achieve a transformation process in the intended timeframe without engaging in M&A. For ESG-driven transactions, this acceleration can come in two forms: (1) companies may indeed invest in certain assets and enterprises to achieve or (2) improve ESG compliance more quickly. Examples would include the acquisition of waste management facilities to reduce the carbon footprint of the existing operations, but also technology-driven acquisitions to get access to less carbon-intensive production methods.

There is also an important divestment-driven dynamic to be considered: companies may decide to shed certain assets which do not further, or may actively hinder, their ESG compliance. The Energy sector provides a very interesting showcase of this dynamic and shall hence be discussed in more detail subsequently.

2.1 ESG in the Energy M&A industry

In the Energy sector, utility companies are particularly affected by the push towards ESG-compliant business models. Specifically, it is the “E” part of ESG which is most relevant for utilities. As is well known, traditional methods of energy generation using fossil fuels cause very high CO2 emissions.

With their negative environmental impact, and further accelerated by the geopolitical risk, fossil fuels are increasingly falling out of favor. Nuclear power generation, while emission-free, is also not seen as a viable alternative in some countries due to its perceived risk profile. Consequently, utilities face the increasing challenge that their traditional business model, which relied on an asset base that generated very stable returns over decades, can no longer be seen as sustainable.

Just as described in the previous chapter, the solution to this challenge needs to cover at least two aspects: strong investments in renewable energy assets like wind and photovoltaic parks, and divestments of traditional fossil power plants.

Upon closer observation, other strategic options may also exist here: On the one hand , it might prove very difficult to find a buyer especially for older fossil power plants, since selling an asset that is not ESG-compliant to a third party can easily be perceived as mere “greenwashing”. At the same time, the alternative, a sunsetting approach to decommission such assets before the end of their useful life, creates challenges of its own, as it is typically costly.

Another strategic consideration could be to try to improve the carbon emission profile of existing assets, for example by transforming coal-powered plants to gas-powered plants (a complex but possible option) or by investing into technologies for capturing and storing CO2 emissions.

We will not focus on the additional strategic options just mentioned to improve ESG compliance – sunsetting, redesign of assets, or the application of new technologies – but rather limit ourselves to the analysis of some of the challenges of the classic investment and divestment processes, which are already quite substantial on their own.

Starting with the investment process, it is important to note that the traditional approach of a utility – erecting a highly expensive power plant in some rural location close to a water source – is fundamentally different to the investment process in renewable energy assets. Starting with the case of an investment in wind turbines, a very comprehensive and specialized process is required to identify a suitable location. Furthermore, such locations are typically not state-owned, and using them for the construction of a wind park hence requires extensive negotiations with various stakeholders. Nor is it easy, at least in most European markets, to identify locations of sufficient size to develop a wind park which in terms of power generation capacity is in proximity to a fossil-powered plant.

2.2 Transactions in renewables companies in Europe

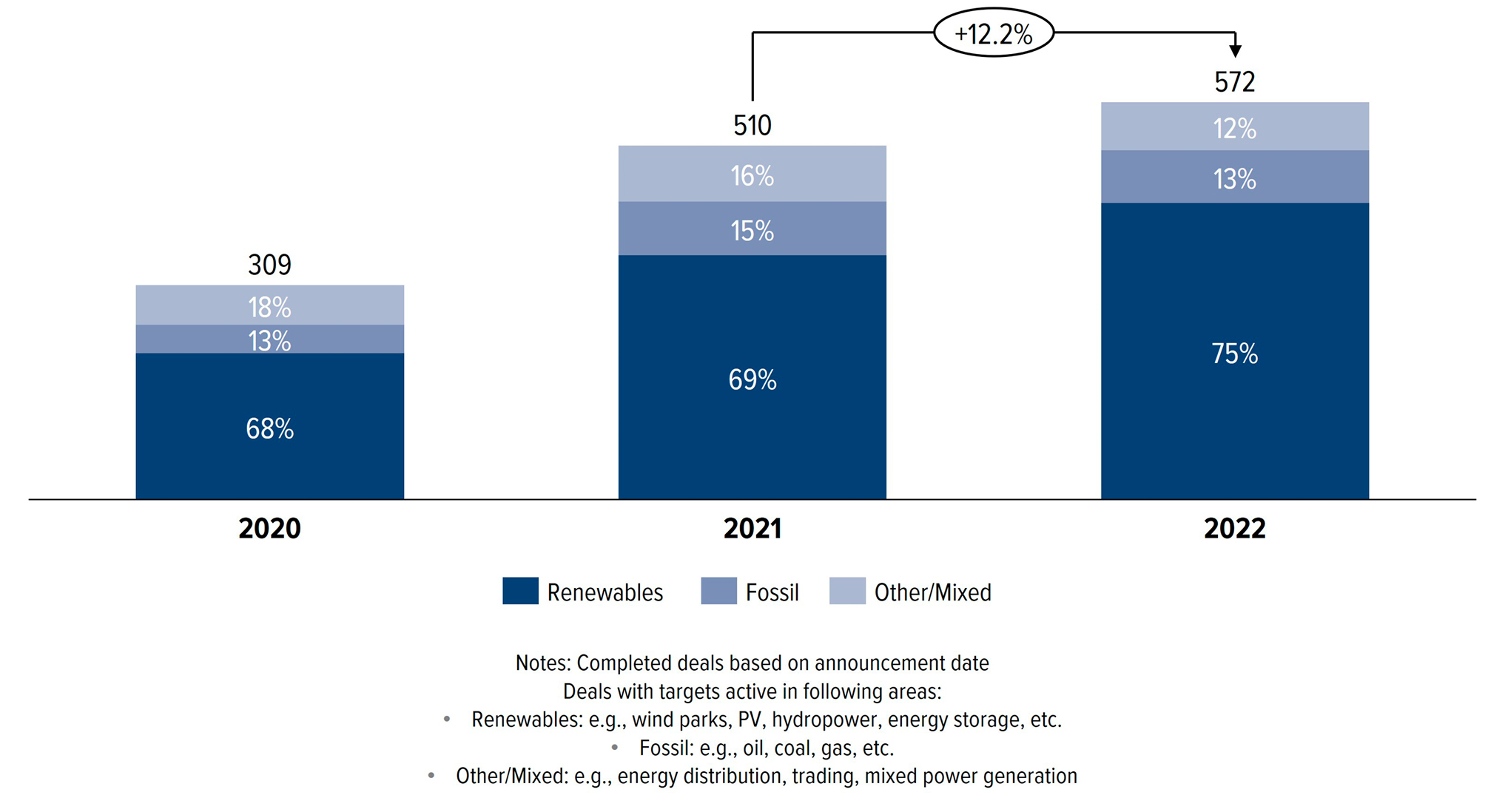

Analyzing the recent deal history in the broader European Energy sector, it is far more common for companies to try to transform their portfolio by acquiring renewable assets rather than divesting their carbon intensive assets. Several notable ESG-focused transactions and investments have been made in recent years which account for around 68 to 75 percent of all deals in the Energy sector in 2020-2022. The number of players active in renewables development and the diversity of the competition has increased significantly in recent years. Consequently, we expect one of the main drivers in M&A in the coming years to be energy majors or similar players greening their portfolio by acquiring assets in the hydrogen, wind, solar, or carbon capture area. One example is the $2.3bn acquisition of Spanish solar and wind developer Eolia Renovables by French utility company Engie in 2021/22. The transaction gives the buyers control over 899 MW of operating solar and onshore wind farms and a 1.2-GW pipeline of projects. Already in 2019 Engie sold their last European coal plants in Germany and the Netherlands to US investment firm Riverstone.

Source: Mergermarket, AlixPartners Analysis

3 ESG framework for M&A processes

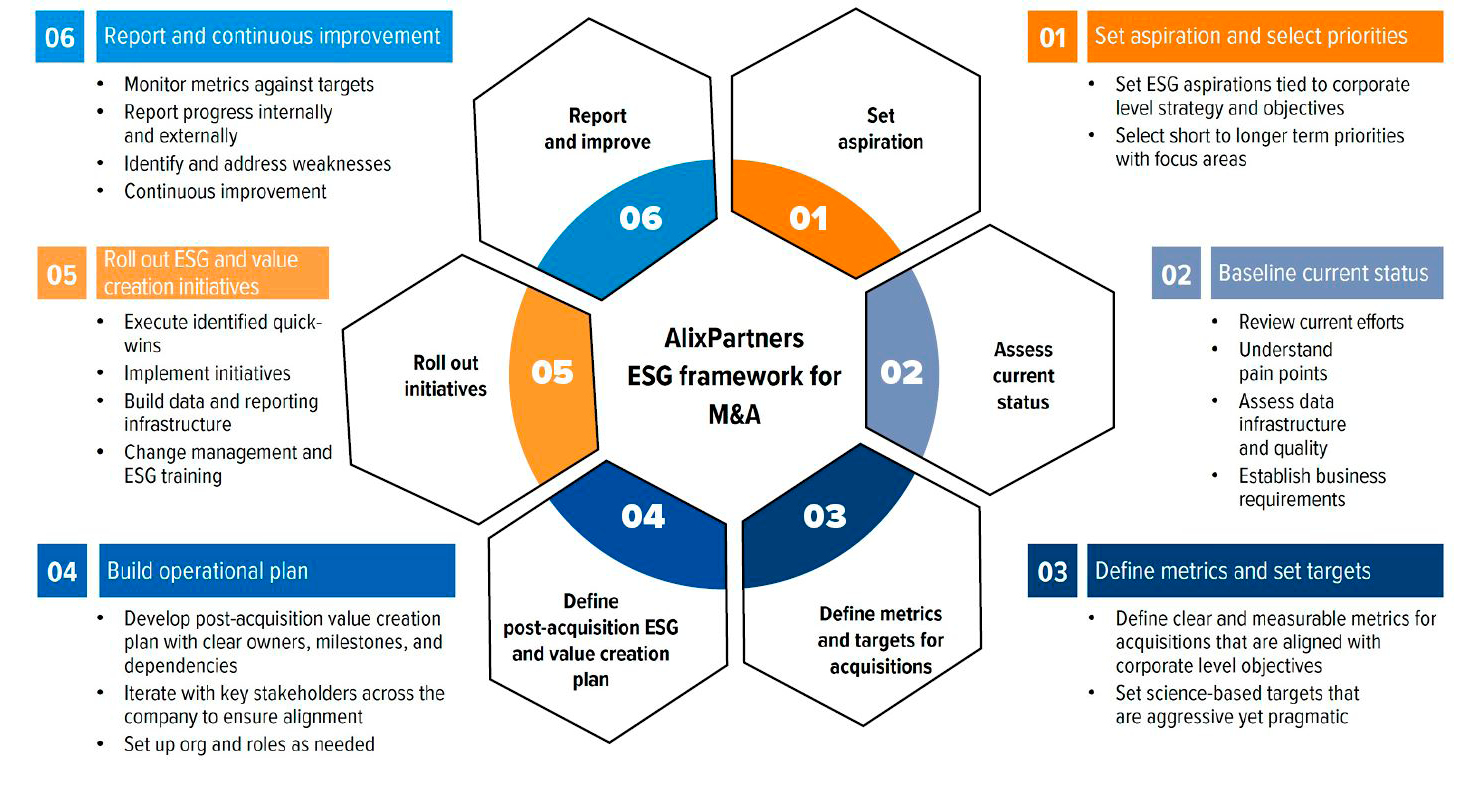

M&A is an accelerator for achieving ESG targets. At AlixPartners, we have developed a transparent framework for integrating ESG in the M&A process with six distinct phases.

The first phase involves establishing ESG goals aligned with the company’s strategic objectives with a clear view on short- and long-term priorities and focus areas. Next, it is necessary to assess the current status of ongoing efforts, evaluating the data infrastructure and quality as well as understanding core business requirements. This also includes identifying pain points, both internally within the company and externally driven by market forces or regulatory requirements. Establishing clear and quantifiable metrics that are consistent with the overall corporate mission and ESG aspiration is a critical part of the third phase, setting objectives that are aggressive yet pragmatic for a quick implementation. The fourth phase involves establishing a comprehensive plan for post-acquisition value creation including well-defined owners and measurable milestones while keeping close coordination and alignment with key stakeholders. ESG initiatives are then executed in the fifth phase, with an initial focus on quick wins and the set-up of a suitable reporting infrastructure. Finally, to drive continuous value creation, monitoring metrics against defined targets and proactively identifying and addressing any weaknesses or shortcomings is vital for success of the M&A strategy.

The AlixPartners ESG Programme Lifecycle

Source: AlixPartners

4 Outlook

It can be anticipated that the regulatory pressure regarding ESG is further increasing. The recent announcement by the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS) of new global sustainability and climate disclosure standards to be effective by January 2024, the EU’s increased focus on ESG reporting and supply chain risks through the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD), and the discussion paper on the future regulatory regime for ESG ratings providers by the UK Economic and Finance Ministry are a few examples to illustrate that companies in the Energy sector can expect increased regulation and scrutiny in the next years.